A cookbook is an invitation; at it’s most basic, an invitation to try an unfamiliar ingredient, learn a new skill, or a new approach to an old favorite. In the ones I like best—like all books I like best—it is also an invitation to a story, with personal reflections and insights on history, landscape, culture, traditions. In other words, there is life in the pages.

A cookbook is an invitation; at it’s most basic, an invitation to try an unfamiliar ingredient, learn a new skill, or a new approach to an old favorite. In the ones I like best—like all books I like best—it is also an invitation to a story, with personal reflections and insights on history, landscape, culture, traditions. In other words, there is life in the pages.

This series, Cooking the Books, is about the experience of accepting that invitation: not as a chef or expert, but as a home cook.

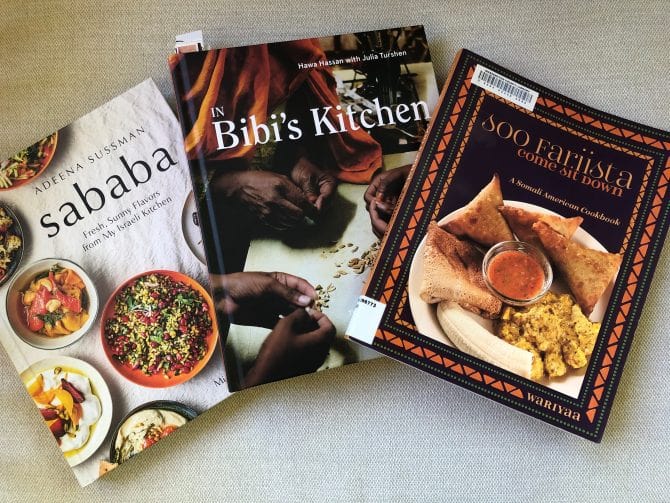

In that spirit, this month I started out cooking from two books, Sababa and In Bibi's Kitchen, both of which are available from the library and are on my bookshelf at home (actually, more off the bookshelf than on it, a good sign). As often happens, questions raised in one cookbook lead you to another. This time, my first try at making Sabaayad (Somali Flatbread) from In BiBi’s Kitchen led to discovery of a third cookbook at the library, Soo Fariista: Come Sit Down , written by a group of Twin Cities-based Somali youth and published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press. (See accompanying audio story).

Sababa is a collection of recipes by Adeena Sussman, who was born in Northern California and now lives in Israel. As the book’s photographs beautifully convey, it celebrates the “sunny flavors” of the Middle East. Many dishes are inspired by her love of Shuk HaCarmel, a Tel Aviv market in her neighborhood whose origins go back nearly 100 hundred years. It was published just a few years ago, in 2019, which seems like eons, given the events that have unfolded since then.

I reach out to Sussman by email in late May, and am happy to hear back from her. (The idea that we can so easily connect with someone 8 hours ahead in time and over 6,000 miles away still amazes me). Shuk HaCarmel, she writes, “was impacted by Corona, and the recent conflict also made for an empty market.” Now, the market was once again “filled with vendors and customers of all colors, religions, and nationalities,” with cherries, apricots, and watermelons in season.

How would she characterize the regional influences on Israeli food, and on her cookbook, Sababa, in particular? She responds, “Israeli food is a heavy helping of Palestinian and other Arab cuisines, as well as the hundred Jewish immigrant cultures that call Israel home. … I definitely see a through-line between my California upbringing and Tel Aviv, in terms of the focus on fresh, seasonal, plant-based cooking.”

In the cookbook, Sussman shares her take on dishes drawn from these “sunny flavors” of the Middle East. Sababa, she explains in the introduction, is derived from an Arabic word meaning “great” or “wonderful,” now commonly used to describe a state-of-mind where everything is cool.

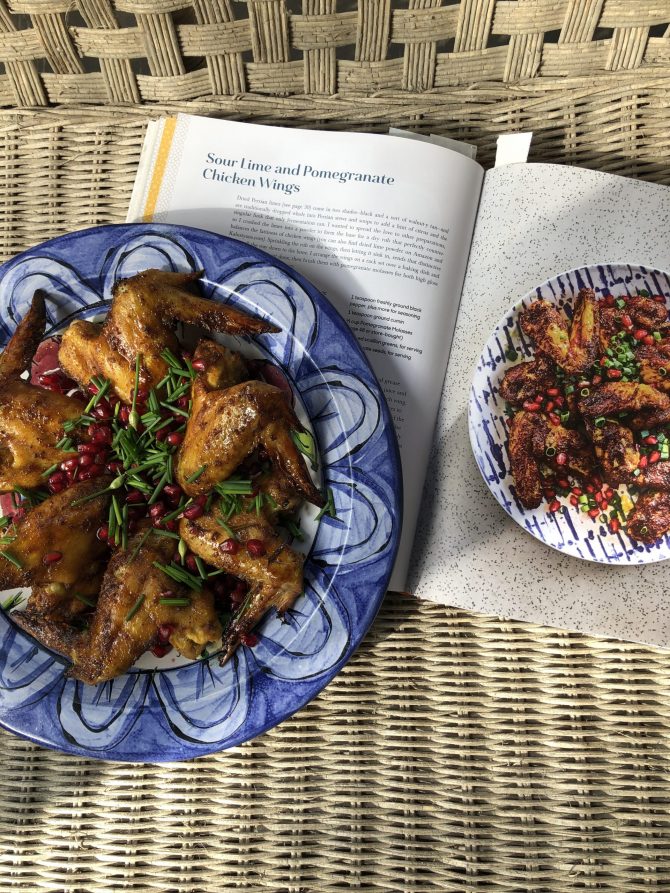

I confess that I am not very obedient when it comes to cookbooks. In fact, somewhere along the way I developed the habit of starting at the end of a book and flipping back toward the front, like the first pass through a Farmer’s Market, scanning to see what catches my eye. With Sababa, my first pass goes like this: Peach Kuchen (Wait until peaches are in season…late July?); Thyme-Roasted Apricots with Whipped Goat Cheese (Roasted apricot pits, that’s a new one); Triple Ginger Persimmon Loaf (Had me at Triple Ginger, persimmon would be a first); Pumpkin-Vegetable Stew with Easy Homemade Couscous (A long ingredient list, some condiments that would require prep—fresh Moroccan pickles, preserved lemons—advice to cut the vegetables in large pieces “so they’re sexy,” and to use a gardening soil sifter for the couscous if you don’t have a “kish kash.” That would be me.); Chard-Wrapped Fish with Lemon and Olive (Beautiful, bright green packets, would be fun for guests; wait, what’s a guest, again?); Sour Lime and Pomegranate Chicken Wings (Hmm, Persian lime powder, track that down); Mushroom Arayes with Yogurt Sauce (Gorgeous grilled, mushroom-stuffed pitas); Hot Date, Kumquat, and Kashkaval Focaccia Pizzas (Not that kind of hot date. Kashkaval? Oh, a sharp cheese. Yeasted dough a little daunting, but it’s meant to have an irregular shape. Good, it surely would).

Already, a tuft of torn scrap-paper strips marking promising recipes pokes up from the binding of the book. I narrow it to a few dishes that I aim to try if I can round up the ingredients: the Sour Lime and Pomegranate Chicken Wings and the Hot Date, Kumquat and Kashkaval Focaccia.

Cookbook authors will offer ideas for readily available substitutions, but I try to honor the original, authentic ingredients when possible. That usually requires looking beyond the big box food stores, where offerings can be meager and limited to designated ethnic sections. [Ok, sidebar. Hasn’t the label “ethnic” lost its meaning in this context? It’s defined as “relating to a population subgroup (within a larger or dominant national or cultural group) with a common national or cultural tradition.” So, by definition, grocers would need to regularly reorganize the shelves as the make-up of our population changes. Maybe they do? Maybe if we went to the store in the early morning hours we would overhear managers debating in the aisles, recent census data in hand, with conversations like: “Wait, this isn’t a subgroup anymore, should we move it to the dominant section?” and “Dang. Where do we put the Polish sausage now?”]

List in pocket, I decide to start with Bill’s Imported Foods, opens a new window on Lake St. in the Uptown area of Minneapolis, owned by the Tirokomos family. A friendly young man working the counter says that he is not a member of the family, but “in the 15 years I’ve worked here, I’ve always been treated like one.” (When I later call the store I talk to Gregory Tirokomos, who describes the store’s stock as mainly Mediterranean and Middle Eastern foods. I ask how long they’ve been in business, and he answers with a droll “a long time.”)

While here, I do find many items on my list: Bulgarian Kashkaval cheese, pomegranate molasses, Medjool dates, dried Persian limes, Diamond brand Kosher salt, and (naturally) items not on my list. The latter includes a few Greek Kourabiedes cookies, wrapped up to go. I make the mistake of taking a bite it in the car, discovering too late that it is piled high with an unexpectedly generous layer of powdered sugar that is soon EVERYWHERE. Not really a problem, except that I will be a little over-decorated at my next stop, Joyful African Foods, opens a new window on White Bear Ave. in St. Paul.

This is where I hope to find ingredients for the dishes I’d like to try from my second cookbook pick this month, In Bibi’s Kitchen.

In Bibi’s Kitchen, compiled by Hawa Hassan with Julia Turshen, is a collection of “recipes and stories of Grandmothers from the Eight African Countries that Touch the Indian Ocean.” What’s not to love? A map in the opening pages helps the geographically challenged. Moving north to south along the continent’s eastern coast, are Eritrea, Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique and South Africa, Madagascar, and Comoros. The beauty of the book is its focus on the individual bibis (grandmothers) and their stories. Thankfully, many chose to share their everyday favorite foods that they considered easy to make. It’s truly remarkable how the authors and their team gathered content for the book, sometimes interviewing by Skype with photographers and translators on location in Africa, sometimes filming with their phones to try to capture the steps of making a dish. In some cases, they interview women who have immigrated to the U.S. from their home countries, noting, “It’s about sustaining a cultural legacy and seeing how food and recipes keep cultures intact, whether those cultures stay in the same place or are displaced.”

For author Hawa Hassan, who was born in Mogadishu, spent time in a refuge camp in Kenya, and was separated from her family when she had a chance to come to Seattle at age 7, engaging with traditional foods has been part of her journey to “understand herself in a cultural arc.” Both Hassan and Turshen were determined to let the bibis speak for themselves in the book. As readers, we’re encouraged to create our own new traditions with the recipes. “We believe that when you read their stories and make their recipes, you will carry their torches.”

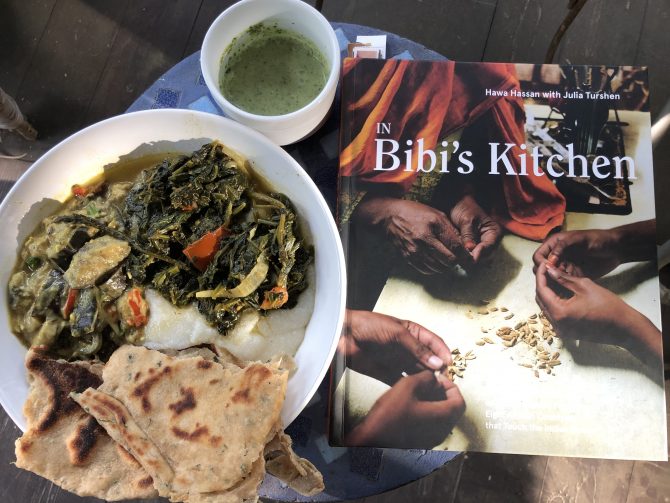

The women speak of home and community and family, and of course, cooking. We meet Ma Jeanne, from Madagascar, who is asked “Who taught you how to cook?” and answers “It’s inside of me.” Ma Maria from Mozambique is asked “Do you enjoy cooking?” and answers, “Yes, I like it a lot, too much.” Her recipes are the ones that especially call out to me, including Tseke com Peix Frito (Local spinach with curry sauce and crispy fried fish) and Xima (cornmeal porridge). Ma Halima, from Somalia, now living in Minnesota, offers her recipe for the indispensable Sabaayad (Somali Flatbreads) needed to soak up all the good sauces. Ma Shara, who is from Tanzania and runs a cooking school in Zanzibar, shares her Quick Stewed Eggplant with Coconut. Author Hawa Hassaz offers Xawaash (pronounced HA-wash) a spice mix that every cook makes a little differently and that “touches just about every Somali dish,” as well as Somali Cilantro and Green Chile Pepper Sauce. I had originally intended to try one or two recipes from each cookbook this month. That now feels impossible.

Ingredients for all of these recipes make up my second list for the day, which I pull out as I head to Joyful African Foods. Note to self: powdered sugar only smears worse when you try to wipe it off.

I might note, this is an interesting time, pandemic-wise. The Governor has just lifted the mask mandate, but mayors in Minneapolis and Saint Paul have instituted their own. I wear one, and people still wear masks in the stores I visit.

Joyful African Foods is self-described as a convenience store and African grocery, tucked between other businesses in a little strip mall. As I enter, I am of course mindful of the fact that “African Foods” refers to a continent. It’s not likely I’ll find all the ingredients from the countries that the cookbook focuses on. But it’s a good place to begin. I see that there are mostly shelf-stable foods and frozen foods, so I will plan to pick up the widely available produce (eggplant, peppers, onions etc.) elsewhere.

Ok, the list.

I choose the ground white corn (ugali flour) that I hope is what Ma Maria might use for her xima. I eye the pumpkin leaves in the freezer, but opt for the spinach (days later going back for the pumpkin, you know how that is). There are meats—like goat—in the freezer, which I have enjoyed at Ethiopian restaurants with injera bread, but are not on my list. I do put a whole frozen mackerel in my basket, and pick up fresh spices for the Xawaash mix, even though I have many of the same spices at home. Fresh spices can make all the difference, and are offered here at a very good price. If I use old spices, I wouldn’t be giving the bibis’ recipes their due.

There are half a dozen men and women in line at the cash register, chatting together and laughing. Even with everyone wearing masks, it feels like an antidote to the year of relative isolation. I am in no hurry for this line to move, and for a long time, it doesn’t. Others join the line behind me. When I eventually work my way to the front, I tell the cashier I like the name of the store. The man next to me in line says, “Yes! Joy is the foundation of daily life.”

Back home, I am aware of the scent of spices drifting in the air, a mix of the familiar and the unfamiliar. I haven’t even begun to cook, and already, the kitchen is transformed, and so am I.

Ma Halima’s Sabaayad (Somali flatbreads) from In Bibi’s Kitchen. What would she think of them, I wonder?

Ma Halima’s Sabaayad (Somali flatbreads) from In Bibi’s Kitchen. What would she think of them, I wonder?

Add a comment to: Cooking the Books with Laurie Allmann: Sababa, In BiBi’s Kitchen & Soo Fariista