Taken collectively—or even individually—the geographic scope of these cookbooks is hilariously ambitious. But, as Alford and Duguid write in the preface to Mangoes & Curry Leaves, “We can’t pretend to know all about this incredible food from the inside out, but we do know it intimately from the outside looking in.” The dishes they share were gleaned from more than three decades of this (then) Toronto couple’s adventures, often on foot or by boat, in one-on-one conversations with local people. The two are seasoned travelers, serious researchers, avid listeners, and wonderful to join in the pages of these books: in part because they don’t just “swan in and swan out” of places to capture a photo or recipe. As Duguid reflects in a conversation with Andrew Zimmer years later, “my biggest ingredient is time.”

Taken collectively—or even individually—the geographic scope of these cookbooks is hilariously ambitious. But, as Alford and Duguid write in the preface to Mangoes & Curry Leaves, “We can’t pretend to know all about this incredible food from the inside out, but we do know it intimately from the outside looking in.” The dishes they share were gleaned from more than three decades of this (then) Toronto couple’s adventures, often on foot or by boat, in one-on-one conversations with local people. The two are seasoned travelers, serious researchers, avid listeners, and wonderful to join in the pages of these books: in part because they don’t just “swan in and swan out” of places to capture a photo or recipe. As Duguid reflects in a conversation with Andrew Zimmer years later, “my biggest ingredient is time.”

While they benefited from the warmth and generosity of people they met along the way, it’s clear they didn’t expect to be any better fed, well rested, or more comfortable than the next person. As reflected in the writing, they were also tuned in to the larger context of social and political issues, past and present.

The 300+ pages of each cookbook are drawn from long stays and many return visits to these regions. I find them to be a great complement to books written by authors whose own cultural heritage is rooted in the same places, since they make no assumptions that anything is common knowledge. Despite their length, the books still have the feeling of being curated: in reading you get the sense that many great stories and dishes had to be left on the cutting room floor in the interest of producing a book that people could actually lift.

We know we are in a good place when our children are awakened early one morning by the sound of their hotel room door slowly squeaking open, and in through the doorway come the horns and the curious head of an enormous water buffalo.

- from Hot Sour Salty Sweet

Hot Sour Salty Sweet: A Culinary Journey through Southeast Asia

It’s been over twenty years since publication of Hot, Sour, Salty, Sweet. The book uses the Mekong River as its through-line, with the couple (and later, their two sons) traveling down the river whenever possible and taking small nearby roads to places “that had been important historically, or places simply too beautiful, or too interesting, to pass by.” Dishes from China, Burma (Myanmar), Thailand, Laos and Cambodia and Malaysia are shared in chapters organized not by region but by types of foods (sauces, soups, salads, noodles, vegetables, fish, etc.).

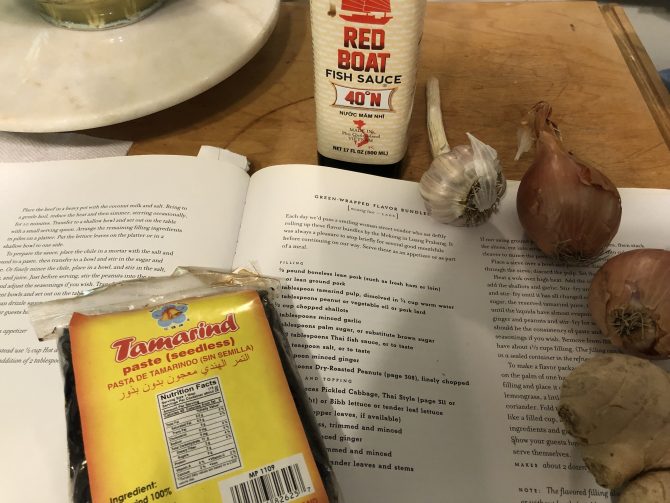

Paging through, I am tempted by many. Shrimp in Hot Lime Leaf broth (tom yum gung) could use my frozen lemongrass from last summer’s garden as well as the bright orange chicken-of-the-woods mushroom we just found growing on one of our oak trees this week. The wild lime leaves it calls for would be a good reason to go to Ha Tien, a nearby Asian grocery. Like bay leaves, they are not meant to be eaten. (My husband has learned to peer into a bowl of soup and ask, “Ok, which parts can I eat?”). In a chapter dedicated to rice dishes, I see that sticky rice has to soak overnight, and works best with the conical steamer basket designed for that purpose (although my bamboo steamer or steamer insert lined with cheesecloth would do). The Spicy Fish Curry with Coconut Milk (pa sousi haeng), Turkey with Mint and Hot Chilies, and Duck in Green Curry Paste all look great, but in a chapter on street food I settle on miang lao, or “Green-wrapped Flavor Bundles.” The filling (a blend of shallots, tamarind, fish sauce, ginger, garlic and ground pork) is designed to be wrapped in pickled cabbage or leaf lettuce, but the recipe notes that the filling can also be used on noodles, topped with peanuts and coriander.

Co-authors Jeffrey Alford and Naomi Duguid didn’t meet for the first time until 1985 (in Lhasa, Tibet), but each had traveled in southeast Asia prior to that time, since the late 1970s. I am mindful, as I read about their travels along the Mekong River described in Hot Sour Salty Sweet, that this of course would have been the era following the Vietnam war, a time when hundreds of thousands of Hmong people fled their villages and became refugees, many eventually making their way to the U.S. and—in particular—to Minnesota.

Given the significance of Minnesota’s relationship with the Hmong community (according to a timeline produced by the Minnesota History Center, opens a new window, the Twin Cities is home to the largest urban population of Hmong people in the country), I wanted to better understand that journey as well as what it has meant for the food traditions of the people who lived it.

Twin Cities-area organic farmer May Yia Lee, a member of the Hmong community, was kind to take time out of the fields to talk. It was a day off from her work as a farm operations specialist at Big River Farms in Washington County, but she was there to take care of her own garden plot on the site.

Lee was born in Laos and lived until the age of 22 in a village 50 km from Vientiane. Together with her husband and young children, she fled from Laos to Thailand, and—still under frightening circumstances—came to the U.S. in 2007. Among her few belongings, she brought a cooking herb she describes as a variety of “duck feet” that she has carefully propagated since then, nurturing it along in greenhouses and sunrooms through the winter until she was finally able to plant it in the ground at Big River Farms for the first time just a year ago. We sit in the shade at a picnic table, where she shares her personal story and her ideas about the connections between culture, health and food. Listen to our conversation here:

Lee was born in Laos and lived until the age of 22 in a village 50 km from Vientiane. Together with her husband and young children, she fled from Laos to Thailand, and—still under frightening circumstances—came to the U.S. in 2007. Among her few belongings, she brought a cooking herb she describes as a variety of “duck feet” that she has carefully propagated since then, nurturing it along in greenhouses and sunrooms through the winter until she was finally able to plant it in the ground at Big River Farms for the first time just a year ago. We sit in the shade at a picnic table, where she shares her personal story and her ideas about the connections between culture, health and food. Listen to our conversation here:

Despite—or maybe because of—her experiences of trauma, grief and loss, May Lee focuses on bringing beauty into the world. Her days are devoted to nurturing living things, caring for her family, embracing organic farming, and (this year) coaxing young plants to survive in record-breaking June heat and little rain.

Despite—or maybe because of—her experiences of trauma, grief and loss, May Lee focuses on bringing beauty into the world. Her days are devoted to nurturing living things, caring for her family, embracing organic farming, and (this year) coaxing young plants to survive in record-breaking June heat and little rain.

She sends me home with a bundle Hmong herbs picked from her garden, to use in making the traditional post-partum chicken soup she described in our conversation. Maternity wards at area hospitals are among her important customers, buying her herbs to make this truly delicious and restorative soup, made with chicken, enough water to cover, salt, pepper, lemongrass and these herbs, all of which were new to me and a revelation.

You can learn more about Hmong herbs in the book, 30 Days of Purification (by Zongxee Lee & May Lee). Produce from Mhonpaj’s Garden, opens a new window is a family organic farm run by May Lee and her daughter, Mhonpaj, can be found at the St. Paul and Mill City farmer’s markets.

Mangoes & Curry Leaves is the 2nd featured book by Alford and Duguid this month. This cookbook invites readers to explore the foods, culture, geologic history and landscapes of Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh on the mainland, and the island nations of Sri Lanka and the Maldives. Honestly, even if you have no intention of cooking any of the dishes in this book, the introductory pages and essays alone would make for a great afternoon read in a comfortable library chair on a hot summer day. And the bibliography and reading list (fiction) could take you in exciting new directions in the months ahead.

Here are a few tastes, from the opening pages: “If you hike in the high ranges of the Himalaya, amid all the rock, snow, and ice, it’s still possible to find fossils of seashells, even sometimes a pale pinkish coral, left from the ancient Sea of Tethys.” … “Figuring out who’s who in the Subcontinent is not an easy task even for people who live here, let alone for foreigners.” … “Nepal, a country roughly the same size as the state of Iowa, has more than fifty different languages.” … “Nearly 75 percent of people in the Subcontinent still live in rural villages, although the urban population is more than three hundred million.”

A lifetime could happily be spent cooking from this book. Dishes are based on what the authors observed in the homes and kitchens they were invited into while traveling and then worked to replicate back at home. Further playing with the proportions is encouraged. In the acknowledgments, Alford and Duguid freely credit the recipes’ origins, offering thanks to people in Udaipur for “market talk and roti lessons,” to the Kathiawari Ribari women for an “encounter in the desert,” and many others whose cooking informed and inspired the contents.

When I first discovered this book, I fell in love with the Bengali five-spice mixture and ever since have kept a jar in my cupboard to enliven any vegetable stir-fry (especially green beans, eggplant, potato and chili pepper). For Cooking the Books, I dive back in and choose Nepali Grilled Chicken, which features a tomato-based sauce with a remarkable depth of flavor, and New Potatoes with Fresh Greens, which uses cayenne and cinnamon, and is made beautiful by the late addition of fresh mint and arugula.

Slow cooked in a tightly sealed heavy pot, North Indian Cauliflower Dum is described by the Alford and Duguid in Mangoes & Curry Leaves as “really a treasure” and surely looks like one, with its heady mix of cumin seeds, ginger, garlic, tomatoes, coriander and more. I make note of it, maybe for when the weather turns cooler.

But now, after a string of days in the 90s, the Mango Ice Cream with Cardamom, or kulfi, begs to be tried. Who am I to say no?

(Also not to be missed: Flatbreads and Flavors, by Jeffrey Alford and Naomi Duguid. Find it at the library!)

Add a comment to: Cooking the Books with Laurie Allmann: “Hot Sour Salty Sweet” and “Mangoes & Curry Leaves”